Hello. I'm Ryan Bigge, a Toronto-based content strategist and cultural journalist. I also dabble in creative technology. And just like Roman on Party Down, I have a prestigious blog.

Thursday, May 27, 2010

My Website Biggeworld.com Returns

My website biggeworld.com has returned from the brink of death. I kinda let the whole thing decay two years ago, switching to this here blog. But I'm pleased to announce that a trim and simple version of my website is now available for your viewing pleasure.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Reprint of DocuBurst and the Future of the Book Article

You are looking at an open book

Created as a course project by a U of T student, this conceptual pinwheel could change the way we read and retrieve information

June 10, 2007 | RYAN BIGGE | Toronto Star

Books are wonderful things, but they tend to release information rather slowly. Bound ink and paper remains stubbornly linear, as sentences unspool across the page in an orderly but time-consuming fashion.

Those seeking a shortcut often rely on book reviews (and, as it so happens, this paper prints many excellent ones each week). But if you're an academic or a lawyer or anyone else with a specialized area of interest, reviews are unlikely to address your info niche. The solution to assessing unfamiliar books or articles might reside in the colourful pinwheels pictured here.

Aesthetics might not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about how to navigate the ever-increasing overload of information. Google Book Search and Amazon's Search Inside feature are great tools – provided you've already read the book in question. For a journalist trying to remember who once boasted about being able to float off the floor like a soap bubble, these databases are a godsend. (O'Brien, as it happens, in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four).

If, on the other hand, you're a first-year university student working on an essay about surveillance, neither Book Search nor Search Inside is likely to steer you toward Big Brother.

For those who spend a significant portion of their lives sifting through the alphabetic silt, DocuBurst (the software prototype that produced these pinwheels) may become as valuable as the scanned pages of Amazon and Google themselves.

At the risk of oversimplification, building an enormous library (be it real or virtual) requires mainly money and time. Effectively navigating the result necessitates innovative approaches to information retrieval and display.

Or, to put it another way, massive amounts of digitized knowledge are useless if they cannot be accessed and assessed quickly and meaningfully.

DocuBurst – the name is a mash-up of document and sunburst – is the brainchild of 28-year-old University of Toronto student Christopher Collins. It's a new method of information visualization (a.k.a. InfoViz) that allows a person to quickly determine the cumulative theme(s) of a given book or document, while at the same time allowing specific keyword searches.

If you're in a hurry, DocuBurst can instantly tell you if a book is sufficiently obsessed with quantum physics, while bookworms can perform detailed literary analysis on a single word, like "nosegay."

"It's a really beautiful book," says Collins, in reference to Jacques Bertin's classic Semiology of Graphics, an exploration of information design that helped inspire DocuBurst. "He talks about the inherent meaning that can be conveyed through data graphics."

The power of information made visual is the difference between an Al Gore speech and an Al Gore PowerPoint presentation. (Of course, in the wrong hands, InfoViz can make things worse, not better, as our indecipherable hydro bills demonstrate.)

Despite their beauty, these pinwheels at first appear strange and opaque, at least without a little explanation. Don't panic. In only a few short paragraphs their mysteries will be fully revealed.

Collins, who is a year away from completing his Ph.D. in computer science, created DocuBurst as a final course project. He began by pouring the contents of a textbook from 1912 called General Science by Bertha Clark into a Java-based toolkit called Prefuse. (General Science, with 20,000 other books, is available as a free e-text download from Project Gutenberg.)

Next, Collins made the textbook searchable. "DocuBurst works like a regular index," explains Collins, "except it's interactive and is able to jump you to whatever part of the document you're interested in."

In normal mode (that is without the pinwheels), a DocuBurst keyword search will include a small window along the bottom of the screen that shows the half-dozen words before and after your search term. This is not unlike the book-scan snippets offered by Google Book or Amazon Inside.

None of this, of course, explains the pinwheels. That's because DocuBurst is two things in one: an interactive index and a method of determining the overall theme of a given book or document. The funky pinwheels will be explained next, after a brief but necessary tangent.

A "treeware" index often includes the infamous "See Also." So if you look up the word Energy, you might be told to See Also: Heat, Radiation and Electromagnetic Radiation.

The structure of DocuBurst pinwheels rely upon an exhaustive type of See Also list generated from WordNet. WordNet is a sophisticated database that groups words into distinct sets of synonyms, a hybrid of thesaurus and dictionary developed by Princeton's Cognitive Science Laboratory. Specifically, WordNet provides "is a" linkages. A cat "is a" kind of pet. Heat "is a" type of energy. This linguistic genealogy provides second, third and fourth cousins removed for any given word.

In the pinwheel pictured on the cover of this section, this results in a See Also list that starts out general and becomes increasingly specific with each additional orbit ring.

Collins isn't the first person to take advantage of WordNet, but he is the first person to transpose the "is a" relationships of a given word across a "radial space-filling graph," that being the technical term for the pinwheels.

From herein, things start getting simpler. Enter a search term like energy and DocuBurst colours the pinwheel based on the frequency of words that are related to the central term. This allows you to visualize the overall theme of a particular document or book.

Without DocuBurst, you're stuck skim-reading or schlepping through the index stuck in the back of a book. Let's say you're interested in intuition, and you picked up Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink. There are about nine entries for intuition, with See Also's for introspection and decision making. Which means you'd need to spend a few minutes flipping back and forth between index and book proper to see if the book met your needs.

Now imagine Blink as a DocuBurst. Given the central search-term intuition, WordNet would create a pinwheel based on synonyms of that word, and then indicate the approximate frequency of related terms and concepts (including, perhaps, ESP) through colouration.

"Our perception of colour ranges is culturally based," explains Collins. "Does red come before blue? I don't know. There's no inherent meaning there. But we do assume that a light colour means less than a dark colour."

Utilizing the same rapid-cognition and thin-slicing skills Gladwell discusses in his book, DocuBurst makes it very easy to determine whether Blink is worth reading.

"We're not particularly interested in people being able to immediately read specific numbers off this graph," explains Collins, in reference to DocuBurst's radial view. "We want to give more of an impression or theme."

The radial space-filling graph can also expand and contract at the click of a mouse. Like most informational visualization projects, DocuBurst is guided by three key principles: overview, zoom and filter, and details-on-demand.

For Collins, information visualization is a tricky mixture of art and science. He borrows techniques from hobbies such as painting, especially colour mixing. In a nod to his M.Sc. in Computational Linguistics, Collins is wearing a red T-shirt with white lettering that reads "I'm a noun!" on the day we meet.

The killer app for these pinwheels will be side-by-side document comparison. Imagine trawling through a legal database, searching for articles about file-sharing. With DocuBurst, you'd be able to see, at a glance, which articles lit up the relevant area of the pinwheel.

This is similar to the relationship between a map of Canada and weather patterns. Superimpose a storm front atop Hamilton and you can tell at a glance that it's a bad day to wash your car. The map is static, the weather patterns fluctuate. In the same way, DocuBurst can take the temperature of a given book or document, thus facilitating rapid pattern recognition.

A cross-comparison feature will require another four to six months of coding, however. In the meantime, DocuBurst's keyword search feature will be road-tested at the University of England this fall, when Collins will be asked to help analyze Victorian literature to determine how often authors used rare words, and in what context. Collins also just entered the Future of the Book contest (www.futureofthebook.org) in which he converted MacKenzie Wark's open source book Gamer Theory into DocuBurst format.

Google anticipates it will take about a decade to scan an estimated 30 million books for its comprehensive library. Which, coincidentally, is about how long it typically takes to implement an interface like DocuBurst so that the general public could comfortably use it at their local library.

Not that Collins is sitting on his hands waiting. He has spent the past year jumping from conference to conference, and is doing a three-month internship at an IBM research centre in New York.

His Ph.D. project, meanwhile, will allow users to compare two-dimensional graphs in a three-dimensional space. Imagine two pie charts able to talk to each other and compare notes, while suspended in space like plates stacked in a dishwasher, and you get some hint as to Collins' ambition.

To try to describe the project further would require many more words that would ultimately fail to convey the elegance and power of the software prototype that Collins let me sneak preview.

Which, come to think of it, perfectly demonstrates the limitations of language and the power and strength of information visualization.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then DocuBurst creates colourful information graphs whose pinwheel patterns are comprised of thousands of words.

(link).

Created as a course project by a U of T student, this conceptual pinwheel could change the way we read and retrieve information

June 10, 2007 | RYAN BIGGE | Toronto Star

Books are wonderful things, but they tend to release information rather slowly. Bound ink and paper remains stubbornly linear, as sentences unspool across the page in an orderly but time-consuming fashion.

Those seeking a shortcut often rely on book reviews (and, as it so happens, this paper prints many excellent ones each week). But if you're an academic or a lawyer or anyone else with a specialized area of interest, reviews are unlikely to address your info niche. The solution to assessing unfamiliar books or articles might reside in the colourful pinwheels pictured here.

Aesthetics might not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about how to navigate the ever-increasing overload of information. Google Book Search and Amazon's Search Inside feature are great tools – provided you've already read the book in question. For a journalist trying to remember who once boasted about being able to float off the floor like a soap bubble, these databases are a godsend. (O'Brien, as it happens, in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four).

If, on the other hand, you're a first-year university student working on an essay about surveillance, neither Book Search nor Search Inside is likely to steer you toward Big Brother.

For those who spend a significant portion of their lives sifting through the alphabetic silt, DocuBurst (the software prototype that produced these pinwheels) may become as valuable as the scanned pages of Amazon and Google themselves.

At the risk of oversimplification, building an enormous library (be it real or virtual) requires mainly money and time. Effectively navigating the result necessitates innovative approaches to information retrieval and display.

Or, to put it another way, massive amounts of digitized knowledge are useless if they cannot be accessed and assessed quickly and meaningfully.

DocuBurst – the name is a mash-up of document and sunburst – is the brainchild of 28-year-old University of Toronto student Christopher Collins. It's a new method of information visualization (a.k.a. InfoViz) that allows a person to quickly determine the cumulative theme(s) of a given book or document, while at the same time allowing specific keyword searches.

If you're in a hurry, DocuBurst can instantly tell you if a book is sufficiently obsessed with quantum physics, while bookworms can perform detailed literary analysis on a single word, like "nosegay."

"It's a really beautiful book," says Collins, in reference to Jacques Bertin's classic Semiology of Graphics, an exploration of information design that helped inspire DocuBurst. "He talks about the inherent meaning that can be conveyed through data graphics."

The power of information made visual is the difference between an Al Gore speech and an Al Gore PowerPoint presentation. (Of course, in the wrong hands, InfoViz can make things worse, not better, as our indecipherable hydro bills demonstrate.)

Despite their beauty, these pinwheels at first appear strange and opaque, at least without a little explanation. Don't panic. In only a few short paragraphs their mysteries will be fully revealed.

Collins, who is a year away from completing his Ph.D. in computer science, created DocuBurst as a final course project. He began by pouring the contents of a textbook from 1912 called General Science by Bertha Clark into a Java-based toolkit called Prefuse. (General Science, with 20,000 other books, is available as a free e-text download from Project Gutenberg.)

Next, Collins made the textbook searchable. "DocuBurst works like a regular index," explains Collins, "except it's interactive and is able to jump you to whatever part of the document you're interested in."

In normal mode (that is without the pinwheels), a DocuBurst keyword search will include a small window along the bottom of the screen that shows the half-dozen words before and after your search term. This is not unlike the book-scan snippets offered by Google Book or Amazon Inside.

None of this, of course, explains the pinwheels. That's because DocuBurst is two things in one: an interactive index and a method of determining the overall theme of a given book or document. The funky pinwheels will be explained next, after a brief but necessary tangent.

A "treeware" index often includes the infamous "See Also." So if you look up the word Energy, you might be told to See Also: Heat, Radiation and Electromagnetic Radiation.

The structure of DocuBurst pinwheels rely upon an exhaustive type of See Also list generated from WordNet. WordNet is a sophisticated database that groups words into distinct sets of synonyms, a hybrid of thesaurus and dictionary developed by Princeton's Cognitive Science Laboratory. Specifically, WordNet provides "is a" linkages. A cat "is a" kind of pet. Heat "is a" type of energy. This linguistic genealogy provides second, third and fourth cousins removed for any given word.

In the pinwheel pictured on the cover of this section, this results in a See Also list that starts out general and becomes increasingly specific with each additional orbit ring.

Collins isn't the first person to take advantage of WordNet, but he is the first person to transpose the "is a" relationships of a given word across a "radial space-filling graph," that being the technical term for the pinwheels.

From herein, things start getting simpler. Enter a search term like energy and DocuBurst colours the pinwheel based on the frequency of words that are related to the central term. This allows you to visualize the overall theme of a particular document or book.

Without DocuBurst, you're stuck skim-reading or schlepping through the index stuck in the back of a book. Let's say you're interested in intuition, and you picked up Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink. There are about nine entries for intuition, with See Also's for introspection and decision making. Which means you'd need to spend a few minutes flipping back and forth between index and book proper to see if the book met your needs.

Now imagine Blink as a DocuBurst. Given the central search-term intuition, WordNet would create a pinwheel based on synonyms of that word, and then indicate the approximate frequency of related terms and concepts (including, perhaps, ESP) through colouration.

"Our perception of colour ranges is culturally based," explains Collins. "Does red come before blue? I don't know. There's no inherent meaning there. But we do assume that a light colour means less than a dark colour."

Utilizing the same rapid-cognition and thin-slicing skills Gladwell discusses in his book, DocuBurst makes it very easy to determine whether Blink is worth reading.

"We're not particularly interested in people being able to immediately read specific numbers off this graph," explains Collins, in reference to DocuBurst's radial view. "We want to give more of an impression or theme."

The radial space-filling graph can also expand and contract at the click of a mouse. Like most informational visualization projects, DocuBurst is guided by three key principles: overview, zoom and filter, and details-on-demand.

For Collins, information visualization is a tricky mixture of art and science. He borrows techniques from hobbies such as painting, especially colour mixing. In a nod to his M.Sc. in Computational Linguistics, Collins is wearing a red T-shirt with white lettering that reads "I'm a noun!" on the day we meet.

The killer app for these pinwheels will be side-by-side document comparison. Imagine trawling through a legal database, searching for articles about file-sharing. With DocuBurst, you'd be able to see, at a glance, which articles lit up the relevant area of the pinwheel.

This is similar to the relationship between a map of Canada and weather patterns. Superimpose a storm front atop Hamilton and you can tell at a glance that it's a bad day to wash your car. The map is static, the weather patterns fluctuate. In the same way, DocuBurst can take the temperature of a given book or document, thus facilitating rapid pattern recognition.

A cross-comparison feature will require another four to six months of coding, however. In the meantime, DocuBurst's keyword search feature will be road-tested at the University of England this fall, when Collins will be asked to help analyze Victorian literature to determine how often authors used rare words, and in what context. Collins also just entered the Future of the Book contest (www.futureofthebook.org) in which he converted MacKenzie Wark's open source book Gamer Theory into DocuBurst format.

Google anticipates it will take about a decade to scan an estimated 30 million books for its comprehensive library. Which, coincidentally, is about how long it typically takes to implement an interface like DocuBurst so that the general public could comfortably use it at their local library.

Not that Collins is sitting on his hands waiting. He has spent the past year jumping from conference to conference, and is doing a three-month internship at an IBM research centre in New York.

His Ph.D. project, meanwhile, will allow users to compare two-dimensional graphs in a three-dimensional space. Imagine two pie charts able to talk to each other and compare notes, while suspended in space like plates stacked in a dishwasher, and you get some hint as to Collins' ambition.

To try to describe the project further would require many more words that would ultimately fail to convey the elegance and power of the software prototype that Collins let me sneak preview.

Which, come to think of it, perfectly demonstrates the limitations of language and the power and strength of information visualization.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then DocuBurst creates colourful information graphs whose pinwheel patterns are comprised of thousands of words.

(link).

Sunday, May 16, 2010

Everyone Loves a Semi-Naked Hipster -- Strip Spelling Bee Debuts in Toronto

Trends: Strip spelling bees are the latest hipster twist on burlesque

Part nerdfest and part peep show, strip spelling bees gain ground

Ryan Bigge | Globe and Mail | Saturday, May. 15, 2010

Peter, a trim young soldier complete with dog tags, is onstage at Toronto's Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, pondering the correct spelling of the word “caduceus.” Sombre quiz-show music plays over the speakers as Peter is informed that a caduceus, which traces back to Greek mythology, is a staff with a double helix of entwined snakes.

“C-A-D-U,” he begins. And then, with an impish grin, “ampersand, tilde, question mark.”

“You spell exquisitely,” says Sherwin Tjia, founder and host of the Honeysuckle Strip Spelling Bee, as the crowd of 80 roars in rowdy approval. A visibly tipsy Tjia manages to tap at his laptop and switch to a soundtrack of raunchy R&B, since the penalty for misspelling a word at this particular spelling bee is removing a third of one's clothing. After three rounds, two winners are declared – best speller and best striptease – which should make Peter's competitive interests fairly obvious.

A slightly more cerebral variant on burlesque, Tjia's Strip Spelling Bee began in Montreal in March of last year. Although it attracted immediate attention, Tjia says it took a few attempts to “work in the kinks” and tweak the pacing. After its Buddies debut last week, Strip Spelling Bee joins Slowdance Night on the list of events that he has successfully imported to Toronto.

“I didn't expect that so many participants would get completely naked,” says Tjia, a medical illustrator and graphic novelist who enjoys creating quirky events for quirky hipsters in his spare time. Contestants get to decide if they want to keep their underwear on or not, and a strict no-booing policy and ban on audience photography help to generate a safe and inclusive atmosphere. Indeed, some of the biggest cheers of the evening went to Adam, a guy whose non-gym physique can be best described as beautifully average.

Unlike Peter, many of the other 12 contestants desperately tried to keep their clothes on, despite facing words such as “flibbertigibbet” and “bouillabaisse.” “This was for the best,” says Laurie, who won as best speller, “since I'm very good at spelling and very bad at stripping.”

Tjia compares Strip Spelling Bee to events like Toronto Roller Derby, the Pillow Fight League and various burlesque troupes. And given the saucy language and queer-friendly atmosphere, Gay Bingo is another obvious comparison point. One of the evening's highlights – other than seeing a leggy Tjia host the event in drag – is the filthy language employed when a contestant asks for their word to be used in a sentence. An otherwise unprintable Tjia riff concluded with “I was a victim of detumescence.”

While Montreal is a great quirk incubator, Tjia is envious of Toronto's professional approach to indie culture, which invariably leads to websites, merchandise and TV deals. Not that he harbours any animus – Tjia was born in Toronto, moved to Montreal 10 years ago to attend university and feels that both cities have a similar sensibility.

Until Tjia decides to go pro with Strip Spelling Bee, however, he must continue the great Canadian tradition of offering modest game-show prizes. Laurie (the best speller) and a woman named Troy (who was declared the best stripper) each received a bottle of red wine, a CD featuring the sound of cats purring for more than an hour and a DVD of Tjia's friend sleeping in a sexy tank top.

As for the other 11 brave contestants? As Tjia notes, they may have lost, but the audience most certainly won.

(Photos courtesy Sherwin Tjia)

(Globe link).

Part nerdfest and part peep show, strip spelling bees gain ground

Ryan Bigge | Globe and Mail | Saturday, May. 15, 2010

Peter, a trim young soldier complete with dog tags, is onstage at Toronto's Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, pondering the correct spelling of the word “caduceus.” Sombre quiz-show music plays over the speakers as Peter is informed that a caduceus, which traces back to Greek mythology, is a staff with a double helix of entwined snakes.

“C-A-D-U,” he begins. And then, with an impish grin, “ampersand, tilde, question mark.”

“You spell exquisitely,” says Sherwin Tjia, founder and host of the Honeysuckle Strip Spelling Bee, as the crowd of 80 roars in rowdy approval. A visibly tipsy Tjia manages to tap at his laptop and switch to a soundtrack of raunchy R&B, since the penalty for misspelling a word at this particular spelling bee is removing a third of one's clothing. After three rounds, two winners are declared – best speller and best striptease – which should make Peter's competitive interests fairly obvious.

A slightly more cerebral variant on burlesque, Tjia's Strip Spelling Bee began in Montreal in March of last year. Although it attracted immediate attention, Tjia says it took a few attempts to “work in the kinks” and tweak the pacing. After its Buddies debut last week, Strip Spelling Bee joins Slowdance Night on the list of events that he has successfully imported to Toronto.

“I didn't expect that so many participants would get completely naked,” says Tjia, a medical illustrator and graphic novelist who enjoys creating quirky events for quirky hipsters in his spare time. Contestants get to decide if they want to keep their underwear on or not, and a strict no-booing policy and ban on audience photography help to generate a safe and inclusive atmosphere. Indeed, some of the biggest cheers of the evening went to Adam, a guy whose non-gym physique can be best described as beautifully average.

Unlike Peter, many of the other 12 contestants desperately tried to keep their clothes on, despite facing words such as “flibbertigibbet” and “bouillabaisse.” “This was for the best,” says Laurie, who won as best speller, “since I'm very good at spelling and very bad at stripping.”

Tjia compares Strip Spelling Bee to events like Toronto Roller Derby, the Pillow Fight League and various burlesque troupes. And given the saucy language and queer-friendly atmosphere, Gay Bingo is another obvious comparison point. One of the evening's highlights – other than seeing a leggy Tjia host the event in drag – is the filthy language employed when a contestant asks for their word to be used in a sentence. An otherwise unprintable Tjia riff concluded with “I was a victim of detumescence.”

While Montreal is a great quirk incubator, Tjia is envious of Toronto's professional approach to indie culture, which invariably leads to websites, merchandise and TV deals. Not that he harbours any animus – Tjia was born in Toronto, moved to Montreal 10 years ago to attend university and feels that both cities have a similar sensibility.

Until Tjia decides to go pro with Strip Spelling Bee, however, he must continue the great Canadian tradition of offering modest game-show prizes. Laurie (the best speller) and a woman named Troy (who was declared the best stripper) each received a bottle of red wine, a CD featuring the sound of cats purring for more than an hour and a DVD of Tjia's friend sleeping in a sexy tank top.

As for the other 11 brave contestants? As Tjia notes, they may have lost, but the audience most certainly won.

(Photos courtesy Sherwin Tjia)

(Globe link).

Wednesday, May 05, 2010

Toronto Star article about "The interplay between art and Ikea"

Picture and a Thousand Words: The interplay between art and Ikea

May 01, 2010 | Toronto Star | Ryan Bigge

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York

It doesn’t take an umlauted gënïus to figure out where this photograph originated. This despite the fact that German-born, San Francisco-based artist Kota Ezawa has processed and transformed the original catalogue image into a soft pastel cartoon.

But Ikea is so iconic that we recognize its well-designed yet affordable consumer seductions even when disguised or distorted. This might also have something to do with its omnipresence — the company now prints nearly 200 million copies of its lifestyle bible each year, making it almost as well circulated as the actual Bible.

It’s hardly a stretch to suggest that Ikea has a pervasive influence that extends beyond our homes (Billy bookshelves and tea light candles) into popular culture itself, like music (“Date With Ikea” by Pavement) and movies ((500) Days of Summer). This might help explain why its unassembled furniture and the consumer utopia it implies have attracted the critical gaze of various artists over the past 15 years. (And for Ezawa, along with Jeff Carter’s mechanized sculptures of blue Lack tables and Kvist bamboo flooring, Ikea supplies both the problematic and the artist’s raw materials.)

Ezawa’s work is entitled “NEW! ($2.99/EA)” and is currently being shown as part of CONTACT, a photography festival held every May in Toronto (www.scotiabankcontactphoto.com). This year’s event is subtitled “Pervasive Influence,” and while that might sound like a reference to Scotiabank’s cultural hegemony (they sponsor the Giller, CONTACT, Caribana and Nuit Blanche), it instead indicates our current era of photographic saturation. As Bonnie Rubenstein, artistic director for CONTACT, writes in this year’s program guide, “The festival acknowledges the all-encompassing role photography plays in our lives, and challenges audiences to explore how it informs and transforms our experience of the world.”

Ezawa is one of a dozen or so photographers in a curated exhibit entitled “The Mechanical Bride” now at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art. This refers not to a screwball robot comedy from the 1930s, but to the (occasionally) screwball ideas of the late media and literary theorist Marshall McLuhan. In his first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, McLuhan analyzed various forms of print culture, including newspapers and advertisements, and tried to tease out hidden meanings. For example, a print ad for Berkshire Nylon Stockings containing a pretty girl and a horse is hardly an innocent tableau for McLuhan: “Juxtaposition of items permits the advertiser to ‘say’ . . . what could never pass the censor of consciousness.”

Today we might recognize this observation as obvious, but McLuhan made his observation back in 1951, when the manipulations of advertising seemed more innocent and less apparent. In an essay about CONTACT’s “The Mechanical Bride” exhibit, Janine Marchessault, a film studies professor at York University, argues that artists like Ezawa are continuing McLuhan’s project: “The mechanisms of persuasion in mass media are revealed through a focus on its conventions and politics behind the scenes.”

The problem today is that the mechanisms and politics of Ikea are far more sophisticated, making them difficult to locate and analyze. Even worse, at least for critics of advertising, is that many of us find the big blue barn’s unique style of manipulation enjoyable. Put another way, it can be hard sometimes to find the necessary skepticism to attack a family-friendly company that offers a $1 breakfast (although until just 11a.m. each morning).

McLuhan’s skepticism, meanwhile, remains an acquired taste. By the time he died in 1980, he had generated a mash of genuine insight, contradictory aphorisms and a half-dozen books, each progressively more confusing than the last. And while it’s impossible to accurately guess what he might have thought about Ikea and Ezawa, he undoubtedly would have mentioned his theory of hot and cool mediums from his 1964 book, Understanding Media.

A hot medium, like photography, is typically information-rich and well-defined, thus requiring less interpretative work on the part of the viewer. What Ezawa has done, McLuhan might argue, is take the hot medium of photography and rework it into a cool medium (like illustration), making the artwork more participatory. This “unphotograph” requires the viewer to more actively interpret the image. Or, as Marchessault writes, Ezawa’s “large-scale transparencies in light boxes, that mimic advertising displays, are no longer recognizable as photographs.”

As luck would have it, McLuhan is currently “hot” (in the buzz-worthy sense) thanks to a new biography written by Douglas Coupland. As a media-savvy, pop-culture obsessed renaissance man who jumps between art, novels, television, movies and non-fiction, Coupland is McLuhan-esque in the best sense of the term, making him well suited to the task of wrestling with the infamous thinker.

Coupland also has work in this year’s CONTACT festival, as part of another McLuhan-inspired exhibit called “The Brothel Without Walls” (the title of which is fodder for another essay entirely). And, it should be noted, Coupland has also found inspiration in Ikea. His first novel, Generation X, included an image of a clip art chair with the caption “Semi-Disposable Swedish Furniture.”

The link between art and advertising isn’t much of a stretch, given the work of Richard Prince, whose photographs recombined Marlboro Man ads. And the link between art and Ikea isn’t tenuous either — the company sells thousands of picture frames each year, along with some tame posters and wall art.

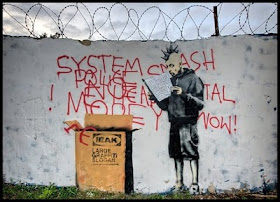

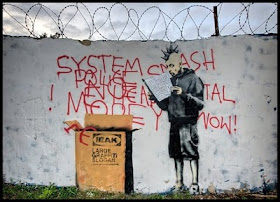

Art inspired by Ikea will continue to grow in proportion to the size and dominance of the company itself. Last September, a new piece by street artist Banksy appeared on a wall in the London district of Croydon, and featured a young punk reading the assembly instructions for a “large graffiti slogan” that was purchased from “IEAK.” And in a tidy twist, art is now starting to inspire Ikea. As the March issue of The Art Newspaper reported, Ikea will be commissioning contemporary artists to create work for a huge new Moscow store scheduled to open in 2012.

In a clever irony, Ezawa takes the precise, staged, too-perfect style of Ikea’s product photography and disassembles the image, attacking the fantasy world with a digital Allen key. Where Ikea requires us to self-assemble the furniture we purchase, art offers us a finished product for contemplation, but we must self-assemble its meaning.

(Toronto Star link).

May 01, 2010 | Toronto Star | Ryan Bigge

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York

It doesn’t take an umlauted gënïus to figure out where this photograph originated. This despite the fact that German-born, San Francisco-based artist Kota Ezawa has processed and transformed the original catalogue image into a soft pastel cartoon.

But Ikea is so iconic that we recognize its well-designed yet affordable consumer seductions even when disguised or distorted. This might also have something to do with its omnipresence — the company now prints nearly 200 million copies of its lifestyle bible each year, making it almost as well circulated as the actual Bible.

It’s hardly a stretch to suggest that Ikea has a pervasive influence that extends beyond our homes (Billy bookshelves and tea light candles) into popular culture itself, like music (“Date With Ikea” by Pavement) and movies ((500) Days of Summer). This might help explain why its unassembled furniture and the consumer utopia it implies have attracted the critical gaze of various artists over the past 15 years. (And for Ezawa, along with Jeff Carter’s mechanized sculptures of blue Lack tables and Kvist bamboo flooring, Ikea supplies both the problematic and the artist’s raw materials.)

Ezawa’s work is entitled “NEW! ($2.99/EA)” and is currently being shown as part of CONTACT, a photography festival held every May in Toronto (www.scotiabankcontactphoto.com). This year’s event is subtitled “Pervasive Influence,” and while that might sound like a reference to Scotiabank’s cultural hegemony (they sponsor the Giller, CONTACT, Caribana and Nuit Blanche), it instead indicates our current era of photographic saturation. As Bonnie Rubenstein, artistic director for CONTACT, writes in this year’s program guide, “The festival acknowledges the all-encompassing role photography plays in our lives, and challenges audiences to explore how it informs and transforms our experience of the world.”

Ezawa is one of a dozen or so photographers in a curated exhibit entitled “The Mechanical Bride” now at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art. This refers not to a screwball robot comedy from the 1930s, but to the (occasionally) screwball ideas of the late media and literary theorist Marshall McLuhan. In his first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, McLuhan analyzed various forms of print culture, including newspapers and advertisements, and tried to tease out hidden meanings. For example, a print ad for Berkshire Nylon Stockings containing a pretty girl and a horse is hardly an innocent tableau for McLuhan: “Juxtaposition of items permits the advertiser to ‘say’ . . . what could never pass the censor of consciousness.”

Today we might recognize this observation as obvious, but McLuhan made his observation back in 1951, when the manipulations of advertising seemed more innocent and less apparent. In an essay about CONTACT’s “The Mechanical Bride” exhibit, Janine Marchessault, a film studies professor at York University, argues that artists like Ezawa are continuing McLuhan’s project: “The mechanisms of persuasion in mass media are revealed through a focus on its conventions and politics behind the scenes.”

The problem today is that the mechanisms and politics of Ikea are far more sophisticated, making them difficult to locate and analyze. Even worse, at least for critics of advertising, is that many of us find the big blue barn’s unique style of manipulation enjoyable. Put another way, it can be hard sometimes to find the necessary skepticism to attack a family-friendly company that offers a $1 breakfast (although until just 11a.m. each morning).

McLuhan’s skepticism, meanwhile, remains an acquired taste. By the time he died in 1980, he had generated a mash of genuine insight, contradictory aphorisms and a half-dozen books, each progressively more confusing than the last. And while it’s impossible to accurately guess what he might have thought about Ikea and Ezawa, he undoubtedly would have mentioned his theory of hot and cool mediums from his 1964 book, Understanding Media.

A hot medium, like photography, is typically information-rich and well-defined, thus requiring less interpretative work on the part of the viewer. What Ezawa has done, McLuhan might argue, is take the hot medium of photography and rework it into a cool medium (like illustration), making the artwork more participatory. This “unphotograph” requires the viewer to more actively interpret the image. Or, as Marchessault writes, Ezawa’s “large-scale transparencies in light boxes, that mimic advertising displays, are no longer recognizable as photographs.”

As luck would have it, McLuhan is currently “hot” (in the buzz-worthy sense) thanks to a new biography written by Douglas Coupland. As a media-savvy, pop-culture obsessed renaissance man who jumps between art, novels, television, movies and non-fiction, Coupland is McLuhan-esque in the best sense of the term, making him well suited to the task of wrestling with the infamous thinker.

Coupland also has work in this year’s CONTACT festival, as part of another McLuhan-inspired exhibit called “The Brothel Without Walls” (the title of which is fodder for another essay entirely). And, it should be noted, Coupland has also found inspiration in Ikea. His first novel, Generation X, included an image of a clip art chair with the caption “Semi-Disposable Swedish Furniture.”

The link between art and advertising isn’t much of a stretch, given the work of Richard Prince, whose photographs recombined Marlboro Man ads. And the link between art and Ikea isn’t tenuous either — the company sells thousands of picture frames each year, along with some tame posters and wall art.

Art inspired by Ikea will continue to grow in proportion to the size and dominance of the company itself. Last September, a new piece by street artist Banksy appeared on a wall in the London district of Croydon, and featured a young punk reading the assembly instructions for a “large graffiti slogan” that was purchased from “IEAK.” And in a tidy twist, art is now starting to inspire Ikea. As the March issue of The Art Newspaper reported, Ikea will be commissioning contemporary artists to create work for a huge new Moscow store scheduled to open in 2012.

In a clever irony, Ezawa takes the precise, staged, too-perfect style of Ikea’s product photography and disassembles the image, attacking the fantasy world with a digital Allen key. Where Ikea requires us to self-assemble the furniture we purchase, art offers us a finished product for contemplation, but we must self-assemble its meaning.

(Toronto Star link).

Tuesday, May 04, 2010

The Dry Wit of MLS

There are so many minor typos and strange turns of phrase in MLS listings that it would be churlish to point them out with any frequency, even though I'm often tempted.

However, writing "hand dryer" instead of handyman or handyperson is really a mistake worth mentioning. Maybe it was an auto-correct or spellcheck thing. Regardless, quite hilarious. I also like how this particular house is not only being sold in "as in" condition, but "where is." Location, location, location.

However, writing "hand dryer" instead of handyman or handyperson is really a mistake worth mentioning. Maybe it was an auto-correct or spellcheck thing. Regardless, quite hilarious. I also like how this particular house is not only being sold in "as in" condition, but "where is." Location, location, location.